BIT/COIN/RARE/EARTH: Data, energy, and extraction across the Arctic, is a multi-sited ethnographic study that looks at the theoretical, logistical, political-economic, and ecological relationships between data, energy, and resource extraction in the greater Arctic through the lens of two case studies— the cryptocurrency mining/high-performance computing industry in Iceland, and the nascent rare earth mining industry in South Greenland. In juxtaposing these sites, I demonstrate how proposed futures for digital technology and renewable energy (of ever bigger data, AI smart grids, ubiquitous solar panels, dominant wind energy, etc.) are indirectly and unevenly co-produced across vast extractive frontiers, and that political discourses of data, energy, and resource extraction cannot be separated. As such, I argue for the building of new regulatory structures that can more justly and equitably address how the inextricably bound futures of digital technology and renewable energy hit the ground—from mine, to data center, to discard, and back again. The dissertation is divided thematically into four sections, each exploring one of the title concepts – BIT, COIN, RARE, and EARTH.

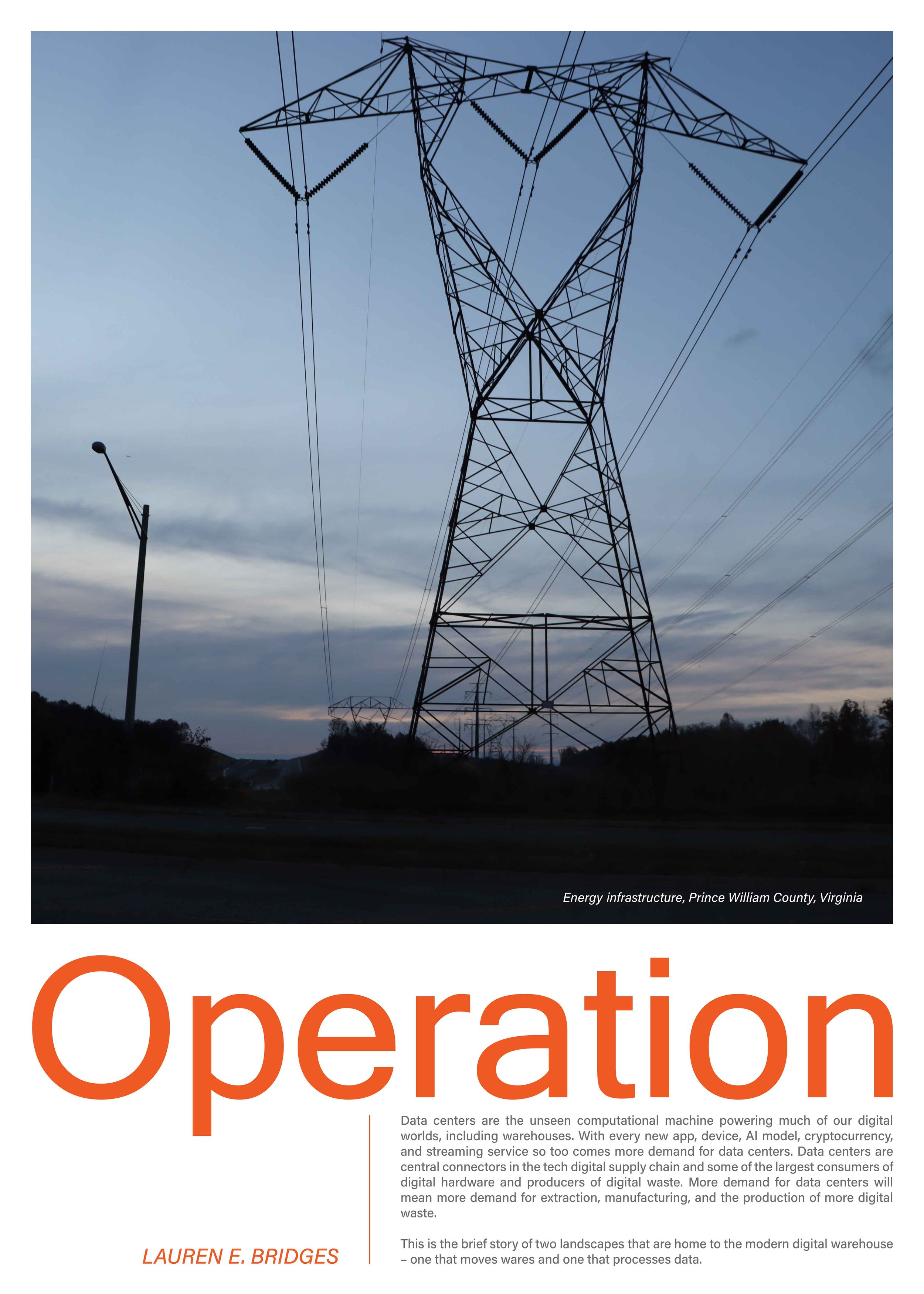

The first chapter, BIT, explores the historical, theoretical, and infrastructural dimensions of computational heat and its management, from its roots in thermodynamic science, to the innards of the circuit, to the industrial heft of the data center—all through ethnographic work on Iceland’s cryptocurrency mining industry. The chapter ends with a discussion on how, while Iceland’s cold climate drives data center growth, global warming is opening up resource extraction for digital and renewable energy futures in other Arctic regions, namely Greenland.

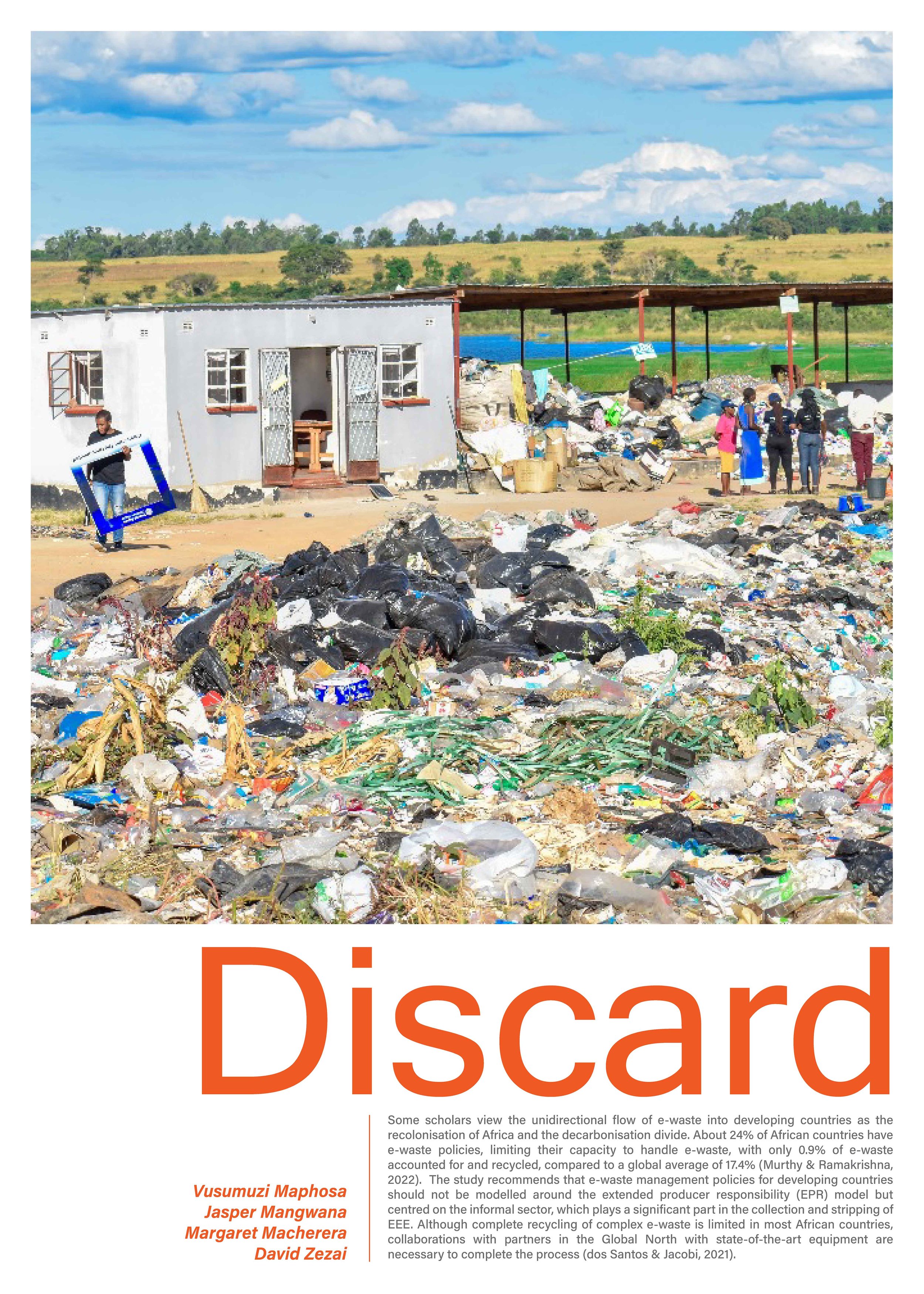

Next, having followed the heat out of the circuit and through the data center, the second chapter, COIN, focuses on data and energy mobilities and logistics, investigating how these infrastructures of data and energy move into place, and who moves them. In logistically situating all the stuff needed to maintain Iceland’s cryptocurrency mining industry, this chapter explores the history and complex political economy of the application-specific-integrated-circuit (ASIC) industry, which undergirds most of the proof-of-work cryptocurrency economy—how ASICs are made, who makes them, and how they travel. Weaved through this will be a tale of social and resource mobility in Greenland, how infrastructures of mobility there have been shaped by hundreds of years of colonialism and forced settlement, and how these histories are informing the futures of resource extraction in the region.

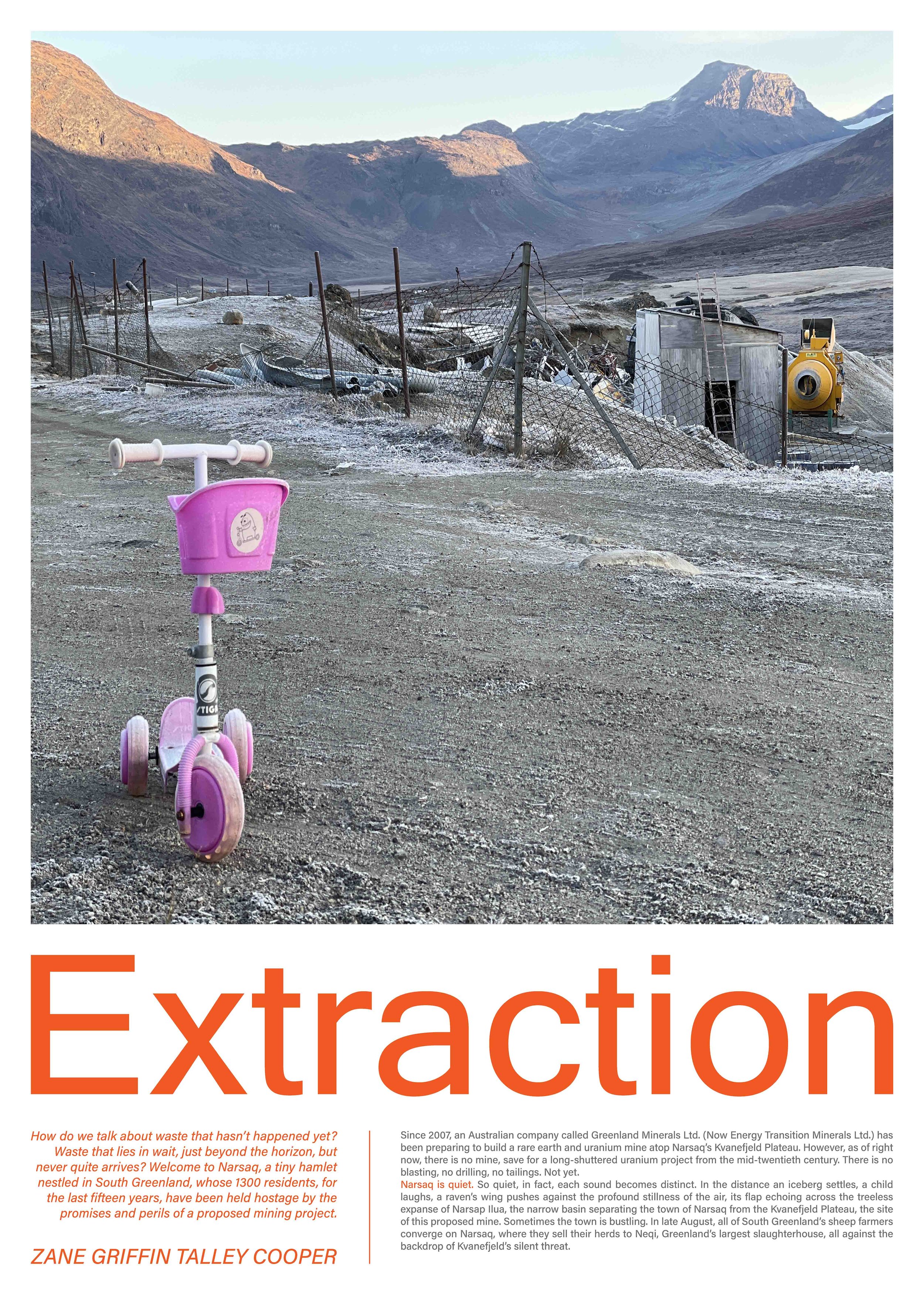

The third chapter, RARE, focuses on the land relations of information infrastructures, considering how the increasingly entangled relationships between data, energy production, and resource extraction manifest geographically. This chapter offers a comparative regional study of cryptocurrency mining infrastructures—in Iceland, Texas, and Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara—arguing that proof-of-work blockchains cannot exist apart from their land relations, and therefore can rarely exist and operate apart from state formations. Here I illustrate how, in regions where cryptocurrency mining infrastructure is deployed at scale, it tends to align with, amplify, and reinforce the values and objectives of the state actors with whom it must partner. I then turn to Greenland, where the global politics and ideological discourses of data and energy are shaping current political and economic landscapes in the region, focusing on the lead up to and aftermath of Greenland’s tumultuous election in April of 2021, which centered around the future of a single proposed rare earth mine near Narsaq.

Lastly, while this dissertation opened with the computational management of heat, the final chapter, EARTH, uses global warming, and the collective visual horror of Greenland’s melting ice sheet, as a frame for discussing how new resource imaginaries for data and energy are inscribing themselves in the warming Arctic.

In sum, these four chapters illustrate how infrastructures of data, energy production, and resource extraction are co-producing each other in ways that cannot be easily contained by linear supply chain imaginaries. I show how cryptocurrency and rare earth mining are ideologically, materially, logistically, and ecologically related, and how their variegated geographies increasingly depend upon one another.